A history of black pioneers in aviation

Ever since the first powered aircraft flight in 1903, African-American aviators have had to overcome racial discrimination to take to the skies. Join us for a look back through history at America’s pioneering black pilots during Black History Month.

During the New Flight Age, many believed black people lacked the aptitude to fly, but a few early pioneers helped to debunk this stereotype. Emory Malick became the first African-American to fly over Pennsylvania in 1911 and some think he was the first black aviator to gain an international pilot’s licence. Others say it was Eugene Bullard, an American military pilot who served in World War I along with Britain’s first black pilot, Jamaican-born Robbie Clarke.

Bessie Coleman was the first African-American and Native American woman to hold a pilot's licence, training in France after being rejected in the United States because of her race and gender. Bessie became a popular stunt flyer and encouraged black people to learn how to fly, famously refusing to perform anywhere racial segregation was still practiced.

Los Angeles and Chicago were springboards for black aviation in the 1930s. Inspired by Bessie Coleman’s legacy, L.A.-based engineer William J. Powell founded a flying school and aero club in her name and wrote a book, Black Wings, to inspire African-American pilots; while James H. Banning and Thomas C. Allen took off from the city as the first black pilots to fly coast-to-coast across America. Meanwhile, John C. Robinson was influencing the next generation in Chicago by launching a dedicated flying club with an airstrip for training pilots.

Also in Chicago was skilled auto mechanic and aeronautical enthusiast Cornelius Coffey. In 1931 he brought together a group of black air enthusiasts to study at the Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical School before setting up the Challenger Air Pilots Association to expand flying opportunities for the black community in the city.

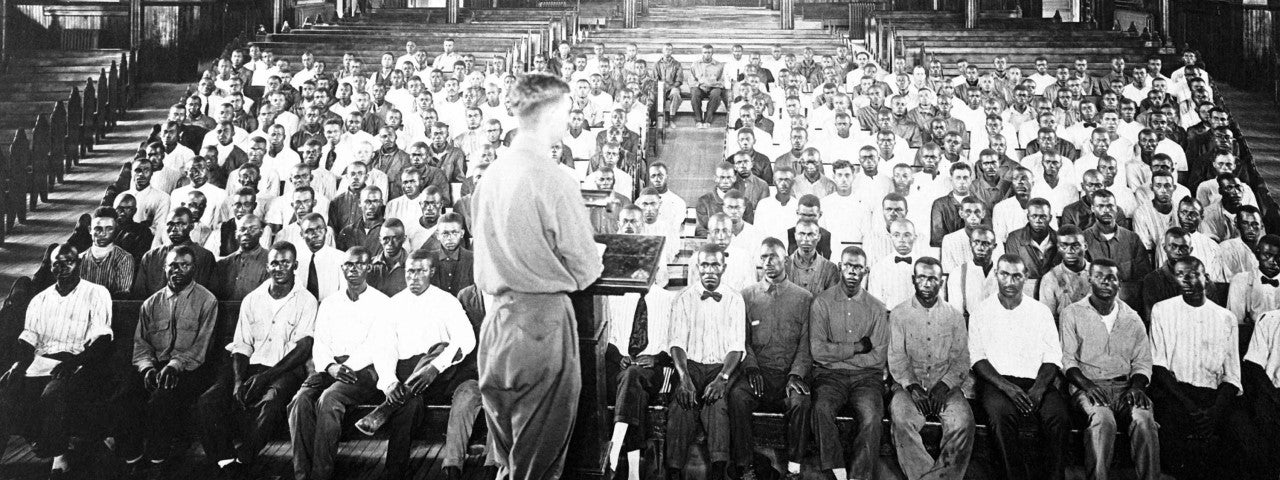

One of its members was Coffey’s soon-to-be wife, Willa Brown, who became the first black woman to receive her pilot licence in the US in 1938. The dynamic duo helped establish the Coffey School of Aeronautics, which quickly received a franchise from the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP). As a consequence of Coffey’s and Brown’s work, Chicago was considered the leading city for black pilot training prior to World War II. Many of the original Tuskegee Airmen, who trained at the famous Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, got their initial training at the Coffey school.

The war was a watershed moment for desegregation in aviation, and not just in America – Britain’s RAF trained nearly 500 Caribbean aircrew, including Distinguished Flying Cross recipient John Jellicoe Blair. Meanwhile, Lilian Bader became not only the first woman, but the first woman of colour to serve in the Royal Air Force. Following the war, The US Air Force became the first armed service in the US to integrate and commit to giving all servicemen equal treatment and opportunity and appointed its first African-American lieutenant general, Benjamin O. Davis Jr., in 1954.

Attitudes continued to evolve as black pilots advanced in America’s commercial sector and in 1956, New York Airways hired the country’s first African-American scheduled helicopter pilot, former military flight instructor Perry H. Young. But major change didn’t come about until 1965, when Marlon D. Green’s landmark victory in the US Supreme Court paved the way for David E. Harris to become the first black pilot for a major US passenger airline.

Black aviators also began breaking barriers beyond the skies in the second half of the 20th Century. Black astronaut Robert Lawrence was selected to a national space programme in 1967, while Guy Bluford became the first black person in space in 1983 when he travelled on a NASA space shuttle. Nine years later, Mae Jemison was the first black woman in space.

From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, there was a noticeable uptick in the number of black pilots, but numbers have since remained fairly stagnant. In fact, according to online recruiter Zippia, African Americans made up just 2.2% of the USA’s pilots in 2010, dropping to 1.6% by 2019, meaning black aviators are still hugely underrepresented.

Aside from expensive tuition costs of around $100,000 per person, a lack of role models and exposure are the most commonly given reasons by experts and instructors for racial inequality among pilots. The profession has been associated with white males for decades and airlines have felt little pressure from consumers to create a better work environment for minorities, but a pilot shortage is beginning to change this trend.

“Most airlines are simply not going to be able to realise their capacity plans because there simply aren’t enough pilots”, says United Airlines’ CEO Scott Kirby. In response, the airline is launching a flight school to hire thousands of pilots, at least half of them women or people of colour. Nonprofits such as Women in Aviation International and the Organisation of Black Aerospace Professionals are also encouraging minorities into piloting, in the hope of diversifying the sector.

Ever since the first powered aircraft flight in 1903, African-American aviators have had to overcome racial discrimination to take to the skies. Join us for a look back through history at America’s pioneering black pilots.

Ever since the first powered aircraft flight in 1903, African-American aviators have had to overcome racial discrimination to take to the skies. Join us for a look back through history at America’s pioneering black pilots.